Scroll to:

FORMAT OF STRATEGY: THE BIGGEST RUSSIAN COMPANIES PRACTICE

https://doi.org/10.17747/2618-947X-2019-3-210-219

Abstract

For citations:

Zavyalova E.A., Kobylko A.A. FORMAT OF STRATEGY: THE BIGGEST RUSSIAN COMPANIES PRACTICE. Strategic decisions and risk management. 2019;10(3):210-219. https://doi.org/10.17747/2618-947X-2019-3-210-219

1. INTRODUCTION

The type and form of the company’s strategy are important components of strategic planning. In the process of formation of strategy the decision maker faces a number of tasks related not to its content, but to its shell: the level of detalization, the level of openness of decisions and the circle of people directly involved in the development of longterm provisions. There is a large number of diametrically opposing opinions on these issues:

- What a strategy should be in terms of duration, publicity, structure, etc.?

- What structural features are characteristic for strategies, what can they look like?

- How does the theory of strategic planning relate to practice?

The main purpose of this analysis was to identify common components in the format of building the strategy of these companies and analyzing the practice of applying strategic planning in real enterprises. The information about the strategy, which was obtained from open sources (usually, on the official websites of companies), may differ from the actual practice of strategic activities within companies. This means that there is not only the relevant existing strategy, but also a strategy that was accepted, which is not executed in practice or published formally in order to divert the attention of competitors from the real one. It is necessary to determine the formats of the existing strategies of companies, which of them are more often used in practice, what is the established strategy, how it relates to the recommendations of the theory. In particular, it is important to consider the approaches to understanding the company's strategy, to analyze the main components of these approaches and to correlate them with the real strategies of companies operating on the market.

2. APPROACHES TO THE UNDERSTANDING OF STRATEGY

The scientific research of the phenomenon of companies’ strategies began in the 1960s. The pioneers of strategic planning include A. Chandler, who investigated the strategies of companies through their external environment, the organizational structure of management (Chandler, 1969). In his understanding the strategy contains the main long-term goals and objectives of the company, in accordance with which a course of action is determined and the resources necessary to achieve these goals are allocated.

A few years later C. Andrews proposed the concept of corporate strategic planning, in which he described the role of senior management in the development and implementation of the development strategy of an enterprise (Andrews, 1971). In this and his other works he deliberately does not give a clear definition of the concept of “strategy” referring to the approach of F. Selznik, who defines strategy as a set of mandatory rules adopted by organizations regarding the methods of action and response (Selznick, 1957).

Somewhat later I. Ansoff in his works carried out a schematization of the strategic planning procedure. As a strategic management tool his matrix makes it possible for the company to determine a strategy for positioning goods and services on the market. The strategy is presented as a set of rules for making decisions that guide companies in their operations (Ansoff, 1979). In other words, it is a combination of quality long-term solutions.

The work of M. Porter (Porter, 1980) occupies a significant position in the theory of strategic planning. It formulates general competition strategies. According to some researchers in this field, the practical side of strategic planning relies mainly on the work of M. Porter. He defined strategy as a choice of development directions for the company depending on the availability of competitive advantages (Chekova, 2010, p. 86). In line with the “five forces of competition” proposed by him and the SWOT analysis, strategy is generally interpreted as defensive or offensive actions aimed at achieving strong positions in the industry. In this sense strategy can also be attributed to a set of quality solutions.

The major theorist of strategic planning G. Mintzberg understood strategy as a plan integrating the main goals of the company, its policies and actions into a single whole (Mintzberg, Lampel, Ghoshal et al., 2002). However, in his early works he argued that a strategy cannot be planned artificially, since it is not the result of analysis, but some kind of synthesis, i.e. it is formed independently, and not at the will of leadership or a team.

A. Thompson and A. Strickland defined strategy as a plan aimed at strengthening the company's position and achieving its goals. It assumes the existence of a goal (non-strategic), ranked higher above the strategy itself (Thompson, Strickland, 2001).

A similar definition was formulated by O. S. Vikhansky: strategy is understood as a long-term, qualitatively defined direction of the organization’s development, which affects the sphere, methods and forms of the company’s activity, the relations within the organization itself, as well as the organization’s position in the environment leading the organization to the realization of its goals (Vikhansky, 1998).

It should be noted that the goal of A. Thompson, A. Strickland and O. S. Vihansky is a priority and not included in it. These are two different (not complementary) concepts.

Any approach to understanding activity planning assumes that long-term solutions will be rational and lead to increased efficiency. A. P. Gradov draws attention to this circumstance. In his view, the company’s strategy is in effective achievement of its goals by economic methods and means. The strategy is formed and functions in accordance with the laws inherent in any system. Combining these two theses we can conclude that strategy should lead to increased efficiency due to a set of interconnected decisions (Efficient strategy, 2006).

G. B. Kleiner understands the company’s strategy as an agreed set of decisions that have a decisive effect on the activities of the company with long-term and irreversible consequences (Kleiner, 2008). Therefore, as in the works of I. Ansoff, this interpretation also reveals a qualitative component in the company's strategy content.

V. S. Katkalo believes that in practical terms strategy embodies the company’s goals of the highest order - its vision and mission (Katkalo, 2008). This interpretation cannot be unequivocally attributed to any approach. It cannot be stated that the vision and mission of a company can be formulated in quantitative terms, but the goal of the company can be in achieving a certain market share, income levels, etc.

A collective definition of strategy looks like a set of strategic decisions in the key areas of the company’s activities: “Strategy is... a well-founded program to improve business organization in four interrelated areas - competitive advantages, organizational transformations, financial optimization, operational improvements that are determined according to the results of strategy development” (Bukhtiyarova, Pavlenko, 2013).

Modern researchers understand strategy as a set of goals, plans and guidelines of their achievement. According to R. Ingram, the company’s activity planning includes an assessment of its mission and long-term goals in order to strengthen the existing practices and to determine the need to develop new programs (Ingram, 2015). R. Rumelt describes strategy as a management’s policy regarding the company’s intentions, as well as the key initiatives or action plans to achieve them (Rumelt, 2016). One sees the understanding of strategy as a set of goals and objectives formulated by and for the management.

Conducting a retrospective analysis of strategic planning paradigms, Magdanov points out that in the 21st century, due to accelerated processes, changes in business models and new types of products, managers understand the company's strategy differently than in the previous century - rather as a long-term project management in order to achieve the set parameters, and not to support the system of "planning - programming - budgeting". In this context, strategy is understood as a combination of a mission and vision of the future, a general goal, strategic goals and objectives, critical success factors and key performance indicators, in other words, not only qualitative factors of long-term activity, but also quantitative ones (Magdanov, 2016).

As the analysis of the concept definitions shows, there are different approaches to understanding the essence of company strategy, which sometimes are diametrically opposed. However, there is a transition from understanding the strategy as a certain target to a set of instructions on how to conduct activities based on the combined key indicator. In this regard, it is necessary to consider the structure of strategy.

3. EXTERNAL ATTRIBUTES OF STRATEGY

In strategic planning the company’s management must answer the following question: when to formulate a strategy? Obviously, the formation of strategy should not begin too early, when the company is still developing chaotically and looking for its niche on the market, but also not too late, when the chaotic extensive development of the company gives way to intensive one. For companies operating in growing, emerging markets, it may not be appropriate to adhere to any particular strategy, and, in some cases, even harmful. As the market matures and the growth slows the development of a comprehensive strategy becomes a vital task for the company (Porter, 1980).

After analyzing the external and internal environment and deciding on the need to formulate or update the strategy it is necessary to highlight the external attributes, for example:

- secrecy or publicity of strategy for the external environment;

- persons allowed to develop strategy (staff, management only, a third-party company), the circle of people familiar with the company's strategy;

- the horizon for the formation of decisions (for a specified period or indefinitely);

- the presence or absence of monitoring activities to implement the provisions of the strategy and their frequency.

As a rule, in a public company (in Russia it is a public joint-stock company (PJSC)), the strategy, if there is one, is used as a tool to increase investment attractiveness. If the company has a plan that takes into account market trends, investors will be more likely to believe in the long term sustainable development of the company. A big company presents a strategy (its updated version) quite widely, for example, during Investor Days or similar events. For other companies such openness may not be characteristic due to non-publicity of their activity or their smaller size. Theoretically, there are different approaches that regulate the degree of openness. I. Ansoff, for example, argued that such plans should be secret, as this could help competitors to calculate further actions of the company (Ansoff, McDonnell, 1988). G. Mintzberg recommended a wide dissemination of information about long-term plans in order to impress competitors with their ambitiousness (Mintzberg, Lampel, Ghoshal et al., 2002).

In developing a strategy it is important to determine a group of eligible people, which might include not only top managers. As practice shows, managers do not always personally form long-term plans. A strategy can be developed by the entire team or outsourced to a company, which provides such services (Business strategies, 1998). For example, in companies of communications industry the development of a strategy is often entrusted to technical departments, which know the development trends of the market from the technical and technological side. The services of strategic consulting are offered by consulting companies McKinsey & Company, The Boston Consulting Group, Bain & Company as the main services and “the Big Four” audit firms (Deloitte, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Ernst & Young, and KPMG) - as additional services.

Some practitioners of strategic planning believe that a strategy should be formed for a certain period of time. At the same time, the theory of strategic planning offers one more option - for an indefinite future (Kleiner, 2009; 2010). The terms of the strategy’s implementation are unknown; it is valid until significant changes in the external or internal environment, when it becomes obvious that its further implementation becomes impractical. With such an approach it is possible not to know in advance how long the chosen strategy will remain relevant - a year, two, three or ten years. In this case, another component of external attributes, such as monitoring activities of the strategy’s implementation, can become especially acute: their presence and frequency.

The compliance of the strategy with the company’s potential and the state of the market can be checked at regular intervals and “according to disturbance”. If control is selected at certain time intervals, it is advisable to indicate it in advance in the process of strategy formation. Between reference checks no additional verification activities are carried out. One can check the relevance of the strategy by identifying the factors that affect the adequacy of the strategy to the current and predicted conditions. The intervals are not predetermined and monitoring activities are assigned individually each time, if necessary, immediately after identifying significant changes in the external or internal environment of the company, for example, when the company’s potential decreases or with changes in market trends, etc.

The analysis of adequacy of the company’s current strategy can be carried out according to such indicators as compliance with the mission, goals, potential, development of the future potential, increasing the competitiveness of the company on the market in the future, the consistency of the elements of the strategy, etc. If the predetermined permissible deviations of indicators are exceeded, it is necessary to adjust the strategy or its individual elements, or the current strategy has completely ceased to satisfy the requirements and one should begin to formulate a new strategy.

The first type of control (interval) may be ineffective. It requires the establishment of an adequate length of intercontrol periods: excessively frequent inspections threaten to turn into permanent control, too rare inspections lead to the danger that obsolescence and inadequacy of the strategy will be detected too late. The second type of control (according to actual compliance) requires a regular monitoring of the external and internal environment of the company, which means additional material and time costs. Obviously, both approaches to duration - time-limited and indefinite - require different structural schemes.

4. THE STRUCTURE OF STRATEGY

Various aspects of strategic planning of companies’ activities have been comprehensively studied for more than a dozen years, but so far in the scientific literature there are no clear answers to the questions directly related to the process of strategy formation. They relate to the appearance of the strategy, its structure and the main components. The preparatory and final stages of formation are described from a general point of view: what one needs to know before starting the development process and how, in the end, the strategy should be described, in how much detail and in which terms.

The analysis of approaches to understanding the essence of company’s strategy and its format makes it possible to group many definitions into the categories “strategy as a target” and “strategy as a process”, as well as their combinations.

The target approach assumes that the strategy ensures the achievement of the ultimate goal after a certain period of time. Quantitative indicators can serve as such goal: market share, income level, profit, etc., which must be achieved by a certain time. By definition, it implies a time period for a series of actions aimed at achieving specified indicators. At the same time, the strategy itself contains information about a specific set of actions aimed at achieving the goal. Representatives of the target approach include A. Chandler, E. M. Korotkov, B. G. Litvak, and others.

The process approach understands strategy as a set of actions that specifically describe the behavior of the company in the process of functioning. A set of options includes: which prices to set, what resources to consume, etc. The implementation of a strategy as a process can be limited to a specific period of time or be unlimited until significant changes in the conditions in which the company operates. In this regard, the process approach involves taking into account the specifics of the environment in which the company operates. This approach was used by I. Ansoff, A. Porter, A. Thompson, G. B. Kleiner and others.

A mixed approach, combining the characteristic components of the target and the process approaches, is manifested in the fact that the goal which it aims to achieve and the means for achieving this goal (a set of decisions, a plan) are added to the strategy. It becomes a kind of guide to action: what to do in a given situation. The main representatives of this approach are G. Mintzberg, A. P. Gradov, V. S. Katkalo, and others.

With a certain degree of conditionality it can be stated that historically the understanding of strategy in theory has been transformed from a set of target indicators to a set of solutions, and now it is understood as a mixture of these two approaches.

As a goal strategy cannot take into account the specifics of its formation’s environment, market peculiarities and company’s potential. It is rather a concept of development in the future expressed in quantitative terms. The lack of a specific set of steps according to the target approach makes this understanding of strategy rather simple, but vague. Company’s employees not only do not get a clear idea of what they need to do to achieve the stated goals, but also run the risk of getting confused. Therefore, it seems more rational to describe the activities of specific companies in the long term in terms of strategy as an action or collective approach.

5. WHAT HAPPENS IN PRACTICE?

The analysis of the adopted strategies of the biggest Russian companies gives an idea of the generally accepted approaches to their formation. The published long-term plans are formed as a “strategy as a process" or by using a mixed approach. These are not pure strategies, but rather slogans or theses of long-term development, information for the press, etc., adapted for a wide range of people. Often such plans do not contain any specificity that could make it possible to make tactical decisions. Why do companies distribute this information, sometimes quite detailed? On the one hand, public companies are obliged to operate openly, but such publicity does not concern the strategic aspects of their activities. As a rule, these “theses of long-term development” fully comply with the development trends of the telecommunications industry, and their open access presentation is not something extraordinary (the exception includes some planned quantitative indicators). In this case it is advisable to recall that there are no unambiguous recommendations on how accessible a strategy should be for a wide range of people, including for competitors. In particular, according to I. Ansoff, the company's strategy cannot be expressed explicitly, because the firm should try to hide its true goals from competitors (Ansoff, McDonnell, 1988). G. Mintzberg considers the option of broad dissemination of information about the chosen strategy in order to deceive competitors or, perhaps, to impress them with ambitious plans. The essence of the strategy should clearly express the goals and objectives of the company’s development for all its employees, but be not be obvious to external players (Mintzberg H., Lampel J., Ghoshal S. et al., 2002).

G. B. Kleiner (Kleiner, Tambovtsev, Kachalov, 1997; Kleiner, 2008) describes the approach to forming the company’s strategy as a set of long-term solutions. To date, he has described 13 types of strategies that together form an integrated company strategy. It can be stated that in practice there is an understanding of the general strategy as a set of thematic blocks. These blocks can be represented either in a chain of vertically structured business processes or in the form of industry components. Such detailing is characteristic of big companies, where diversification does not allow taking into account the specifics of certain areas in the total volume of activities. For example, oil companies are characterized by a breakdown into strategic blocks: exploration, production, transportation, sales, etc. Telecommunication companies prefer segmentation by service and market sectors: private or corporate customers, technologies of providing telecommunication services.

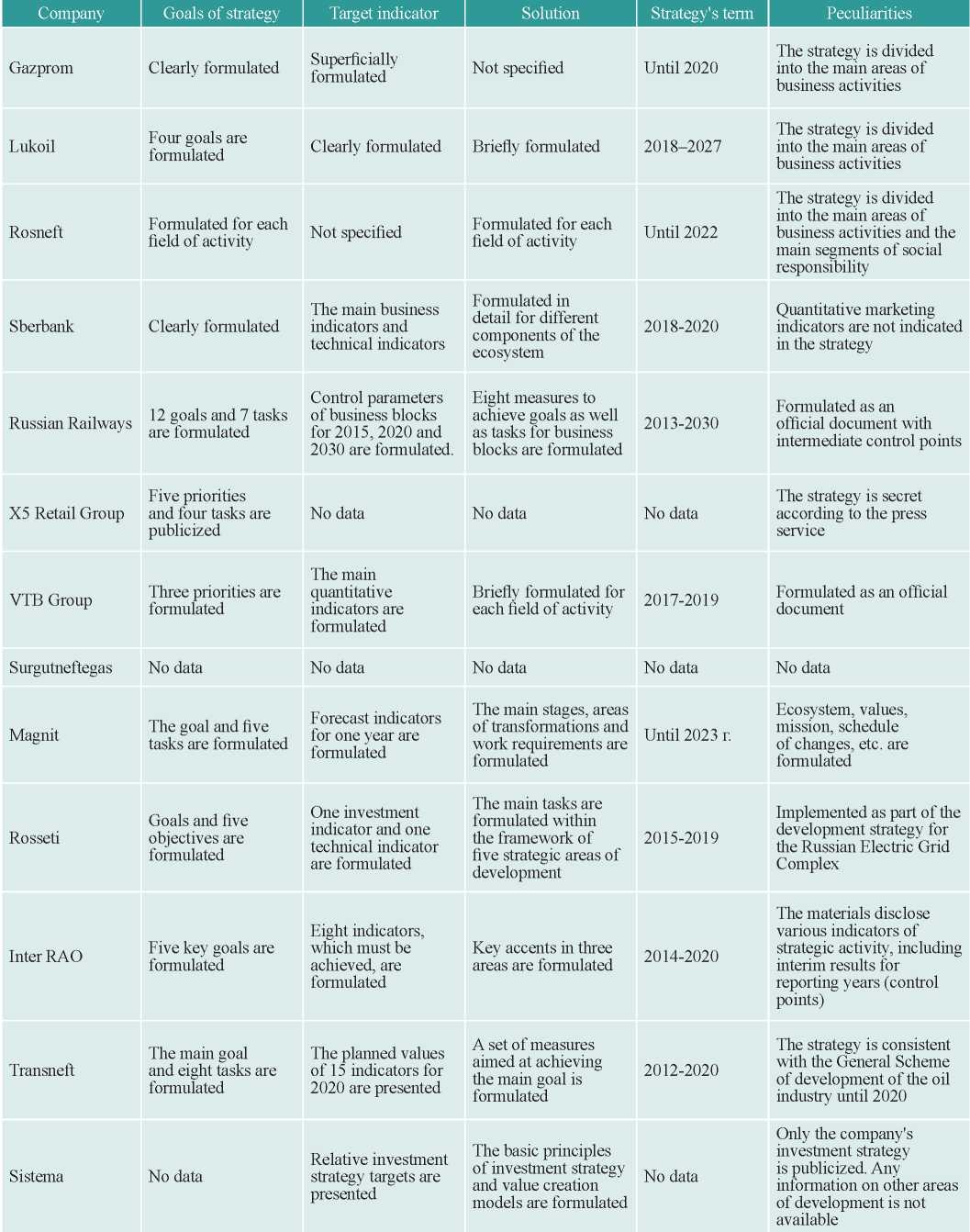

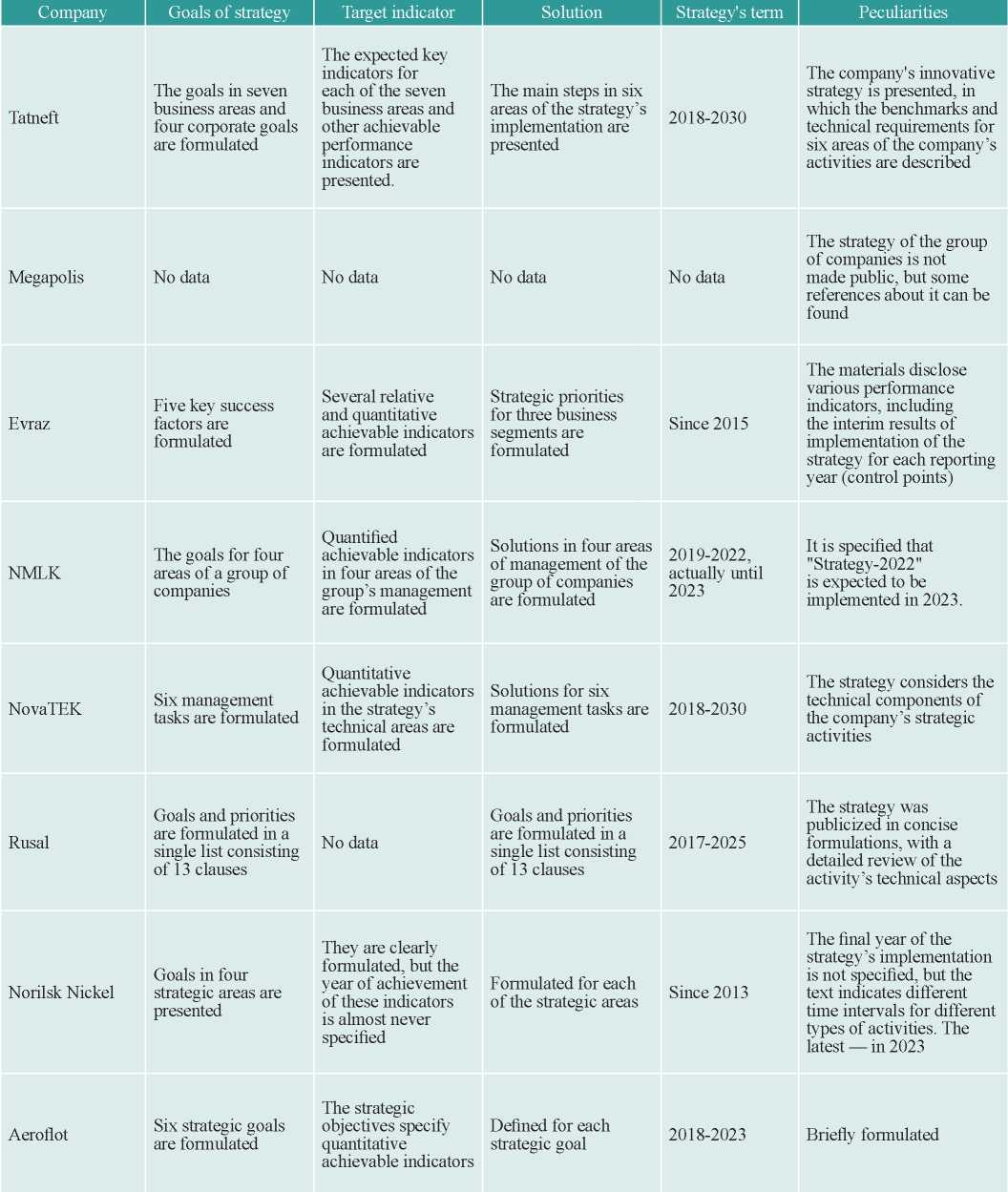

We analyzed the strategies of the biggest Russian companies. The 21 biggest companies in terms of revenues were subjected to the most detailed analysis: Gazprom, NK Lukoil, NK Rosneft, Sberbank of Russia, Russian Railways, X5 Retail Group, VTB Group, Surgutneftegas, Magnit Retail Network, “Russiyskiye setyi”, Inter RAO, Transneft, AFK “Sistema”, Tatneft, Megapolis, Evraz, NMLK, NovaTEK, United company “Rusal”, Norilsky nickel and Aeroflot group of companies (according to the Expert-400 rating).

The main elements of the analysis are:

- publicity or secrecy of strategy (availability in the public domain);

- strategic goal;

- achievable targets based on the results of the strategy’s implementation, as well as intermediate control points (if available);

- intermediate control points;

- the duration of strategy (for a certain interval or indefinite);

- the official status of strategy as a document (Table 1).

This set of indicators was proposed in order to find common points in the strategies of the biggest companies, to understand what kind of real strategies companies have and what their features are.

It is worth mentioning the structuring in the strategies of companies that simultaneously offer a wide range of goods and services. In practice, they consider their structure as a set of solutions or as a set of slogans. Collectively, such strategy can be described as follows: one or several targets are put forward in a qualitative or quantitative presentation along with a certain set of steps to achieve them. In the vast majority of cases a strategy is formed for a certain number of years, i.e. the planning horizon is represented by a time interval (Kobylko, 2016; 2018). For telecommunication companies the actual implementation date does not coincide with the planned one - it is completed ahead of schedule. The approach to the strategy involves not only a specific time interval, but also a reduction in time for its implementation: according to the plan - up to five years, in practice - up to three years. The reasons for this may include:

- a high degree of market uncertainty in the conditions of its intensive development;

- neglect of strategic guidelines for the sake of immediate profits or the perception of strategy as part of the image that does not have a real impact on the functioning and management of the company;

- insufficient elaboration of the strategy, its inadequacy to the changing external and internal conditions of functioning;

- management in "manual mode" closely associated with the personality of the leader;

- the high role of external factors influencing the development of the industry, its target guidelines, and, as a consequence, all key players, etc.

Table 1

The main parameters of strategies of the biggest Russian companies

At the same time, telecommunications companies work exactly as is customary on the international communications market, which means that they are influenced by foreign principles of strategic planning.

As the analysis of practices of the strategy’s structuring showed, domestic companies are not inclined to adhere to theoretical recommendations for making long-term plans. It turned out to be problematic to identify common features of the strategy’s appearance, which may indicate precisely the lack of consistency in the approach.

THE FORMAT OF MODERN STRATEGY

We have identified the following patterns.

- All big companies have formed their strategies (with the exception of Surgutneftegas, which does not mention strategy on its website).

- Most strategies are publicly accessible with varying degrees in detail. Some companies presented fairly detailed strategies with rich illustrative material while others presented mainly their theses. As a rule, websites provide a general understanding of the ways of development for the declared period.

- Almost all companies have formed short-term strategies (mainly up to five years). The exceptions are oil and gas companies (for ten years or more) and Russian Railways (18 years).

- For all publicized strategies strategic goals and objectives were formulated.

- Strategies are often characterized by sub-strategies according to business areas.

- For each sub-strategy (if any) there are some formulated sets of decisions “what to do” or “what tasks to solve” within the framework of this business area.

The achievable quantitative indicators are rarely made public - only the key ones: profits, market share, etc. Some relative indicators are formulated as a percentage of the last year of the strategy’s implementation in comparison with the first one. This aspect of strategic activities of big companies shows a common understanding of strategy as a certain quality document, rather than a set of quantitative indicators for a certain forecast period, which is confirmed by the recommendations of modern approaches to the theory of strategic planning.

The planning of control points is not common for these companies with the exception of only three of twenty companies: Russian Railways (the strategy provides for monitoring activities every five years), Evraz and Inter RAO do not disclose the frequency of monitoring activities, but annually publish reports on the implementation of their strategies. The presented strategies can be adapted for the general public, primarily for investors, and have a very mediocre connection to real strategic goals and objectives; a strategy that is implemented in practice can be very different from the publicized strategy.

It is worth highlighting some industry specifics. In the oil and gas sector companies’ strategies have much in common: strategic goals and objectives are formulated, the strategy itself is divided into separate business areas for which sets of solutions are formed, the implementation period is about five years (with the exception of the strategies of Lukoil and Tatneft, which are calculated until 2027 and 2030, respectively). In the industrial sector the planning horizon is bigger than in other sectors due to the complexity and duration of projects’ implementation, as well as a low dynamics of factors that can have a significant impact on the degree of environmental uncertainty. At the same time, the intensity of changes in the financial sector and retail trade does not make it possible to form plans for the horizon more than 4-5 years. Large retailers (X5 Retail Group, Magnit and Megapolis) show great secrecy in demonstrating their strategic priorities. The strategy of Magnit network describes fairly general provisions, without highlighting any specific action plans, etc., while the strategy of X5 Retail Group contains only a few clauses. This feature is associated with the specifics of the food retail market, suggesting the possibility to copy competitors’ strategic decisions.

As a rule, the published strategy is usually open and short-term containing details of the areas of business activities. Sets of strategic decisions or directions of development vectors are formulated for each area. This notion of strategy can be compared to a birthday cake. It is beautiful, big, multi-tiered and multi-layer, it looks perfect. However, it does have an expiration date, and the taste may not match its looks. Such notion is consistent with modern approaches to understanding the format of strategy and with preliminary (after a survey of 150 respondents) data from the study called “Company strategy: type, format, control points” conducted by CEMI RAS in 2019.

References

1. Andrews, K. R. (1971). The Concept of Corporate Strategy. Homewood, XL: Dow Jones-Irwin. 245 p.

2.

3. Ansoff, H., McDonnell, E. (1988). The New Corporate Strategy. New York: Wiley. 258 p.

4.

5. Ansoff, I. (1979). Strategic Management. London: Macmillan. 236 p.

6.

7. Chandler, A. (1969). Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise. Cambridge: The MIT Press. 463 p.

8.

9. Ingram, R. (2015). Ten Basic Responsibilities of Nonprofit Boards. 3rd ed. Washington D.C.: Board Source. 104 p.

10.

11. Mintzberg, H., Lampel, J., Ghoshal, S. et al. (2002). The Strategy Process: Concepts, Context and Cases. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. 489 p.

12.

13. Porter, M. (1980). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York: Free Press. 396 p.

14.

15. Rumelt, R. P. (2016). Good Strategy/Bad Strategy. New York: Crown Business, 246 p.

16.

17. Selznick, P. (1957). Leadership in Administration: a Sociological Interpretation. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson. 162 p.

18.

19. Thompson, A., Strickland, A. (2001). Strategic Management: Concept and Cases. Boston: McGraw-Hill/Irvin. 1079 p.

20.

21. Bukhtiyarova, T. I., Pavlenko, E. L. (2013). Monitoring vyyavleniya i otsenka kharaktera vzaimosvyazej rynochnykh strategij i strategij setevykh torgovykh predpriyatij // Regional'naya ekonomika: teoriya i praktika. №14. S. 2–8. [Bukhtiyarova, T. I., Pavlenko, E. L. (2013). Monitoring of identification and assessment of nature of interrelations of market strategy and strategy of network trade enterprises. Regional Economics: Theory and Practice. 14:2–8. (In Russ.)].

22.

23. Vikhanskij, O. S. (1998). Strategicheskoe upravlenie. M.: Gardarika. 296 s. [Vikhansky, O. S. (1998). Strategic Management. Moscow: Gardarika. 296 p. (In Russ.)].

24.

25. Kat'kalo V. S. (2008). Evolyutsiya teorii strategicheskogo upravleniya. 2e izd. SPb.: Vysshaya shkola menedzhmenta; Izdat. dom S.Peterb. un-ta. 548 s. [Katkalo, V. S. (2008). Evolution of Strategic Management Theory. Graduate School of Management, St. Petersburg University. 2th ed. St. Petersburg: Publishing House of Graduate School of Management of SPbU. 548 p. (In Russ.)].

26.

27. Klejner, G. B. (2010). Novaya teorii ekonomicheskikh sistem i ee prilozheniya // ZHurnal ekonomicheskoj teorii. №3. S. 41–58. [Kleiner, G. B. (2010). The New Theory of Economic Systems and Its Applications. Journal of Economic Theory. 3:41–58. (In Russ.)].

28.

29. Klejner, G. B. (2009). Sistemnyj podkhod k strategii predpriyatiya // Sovremennaya konkurentsiya. №1. S. 100–118. [Kleiner, G. B. (2009). A Systemic Approach Towards a Business Strategy. Modern Competition. 1:100–118. (In Russ.)].

30.

31. Klejner, G. B. (2008). Strategiya predpriyatiya. M.: Delo. 568 s. [Kleiner G.B. (2008). Strategy of Enterprise. Moscow: Delo. 568 p. (In Russ.)].

32.

33. Klejner, G. B., Tambovtsev, V. L., Kachalov, R. M. (1997). Predpriyatiya v nestabil'noj ekonomicheskoj srede: riski, strategii, bezopasnost'/pod obshch. red. S.A. Panova. M.: Ekonomika. 288 s. [Kleiner, G. B., Tambovtsev, V. L., Kachalov, R. M. (1997). The Enterprise in an Unstable Economic Environment: Risks, Strategies and Security. Moscow: Economika. 288 p. (In Russ.)].

34.

35. Kobylko, A. A. (2016). Kombinirovannyj podkhod k formirovaniyu strategii operatora svyazi kak polisistemnoj kompanii // Terra Economicus. №3. S. 50–62. [Kobylko, A. A. (2016). Combined Approach to Strategy Building of Operator as a Polysystemic Company. Terra Economicus. 3:50–62. (In Russ.)].

36.

37. Kobylko, A. A. (2018). Retrospektivnyj vzglyad na strategii operatorov svyazi // Ekonomika i kachestvo sistem svyazi. №2. S. 4–14. [Kobylko, A. A. (2018). Retrospective Analysis of Telecom Operators Strategies. Economics and Quality of Communication Systems. 2:4–14. (In Russ.)].

38.

39. Magdanov P.V. (2014). Sovremennaya paradigma strategicheskogo planirovaniya // Ars Administrandi. №1. S. 5–16. [Magdanov P.V. (2014). The New Paradigm of Strategic Planning. Ars Administrandi. 1:5–16. (In Russ.)].

40.

41. Strategii biznesa: analiticheskij spravochnik (1998)./Pod obshch. red. G.B. Klejnera. M.: Konseko. [Business Strategies: analytical guide. (1998), ed. by G.B. Kleiner. Moscow: Сonseсo. (In Russ.)].

42.

43. Effektivnost' strategii firmy (2006)/Pod red. A.P. Gradova. SPb.: Spetsial'naya literatura. 413 s. [Effectiveness of the Company's Strategy (2006)./Ed. by A.P. Gradov. St. Petesburg: Special Literature. 413 p. (In Russ.)].

44.

About the Authors

E. A. ZavyalovaRussian Federation

Researcher CEMI RAS. Research interests: Strategic planning, risk management.

A. A. Kobylko

Russian Federation

Leading researcher CEMI RAS. Research interests: Strategic planning, telecommunication economic, system economic theory.

Review

For citations:

Zavyalova E.A., Kobylko A.A. FORMAT OF STRATEGY: THE BIGGEST RUSSIAN COMPANIES PRACTICE. Strategic decisions and risk management. 2019;10(3):210-219. https://doi.org/10.17747/2618-947X-2019-3-210-219